I see society’s pulse in its structures—how they uplift or oppress, unite or divide. The electoral boundary system, stewarded by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), is a structure teetering on collapse.

On September 5, 2035, the Supreme Court delivered a monumental Advisory Opinion striking out IEBC’s application dated July 4, 2024 seeking a determination on the missed boundaries review deadline. The Supreme Court threw the ball back to the IEBC, in essence saying to them, use your collective wisdom or sink in your folly. Add to this the festering wound of Kieni’s 2012 backlash, and the diagnosis is clear: the current framework is unsustainable.

My solution? A separate Boundaries Commission and a radical shift to citizen-driven ward delineation; a reclamation of power by the people. Let’s rewind to 2012. Kieni, a sprawling constituency in Nyeri County, erupted in protest during the IEBC’s first post-2010 review. With 130,000 souls spread across 1,500 square kilometres of rugged terrain, its people demanded a split into two constituencies. Poor roads, scattered villages, and a growing population strained representation beyond breaking.

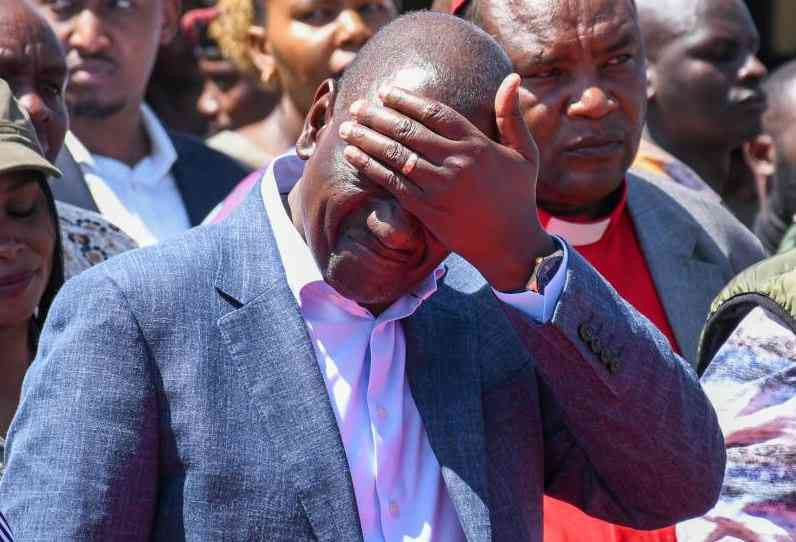

The IEBC, shackled by the 290-constituency cap, said no. Petitions flew, streets filled and leaders like Nemesyus Warugongo cried foul. The refusal wasn’t just administrative—it was a dismissal of lived experience, a cold arithmetic triumph over human need. Kieni’s Kikuyu majority felt sidelined, their voices drowned by a formula that prized population quotas over equity. That resentment lingers, a ghost haunting every boundary debate. Fast forward to 2025. The IEBC has missed its 2024 review deadline—due between 2020 and March 2024, finalised by March 2023 for the 2027 election. Kenya’s population, now likely exceeding 50 million, has outgrown 2019 census data, yet boundaries remain frozen.

Urban giants like Embakasi swell, rural expanses like Kieni stagnate, and IEBC blames a budget shortfall and leadership gaps. IEBC is hoping for a miracle to the boundaries impasse where none exists. Instead, we are stuck in a time warp, governed by a body too stretched by elections to prioritise boundaries.

My vision is twofold. First, we must birth a separate Boundaries Commission, untethered from electoral chaos. This is about clarity of mandate. A dedicated body, like South Africa’s Municipal Demarcation Board, could wield tools like GIS and a Weighted Representation Index—balancing population with infrastructure, poverty, and geography—to craft boundaries that breathe Kenya’s diversity.

A Boundaries Commission would start on a ring-fenced budget and multi-year planning would ensure reviews happen on time, every 8 to 12 years. Separation depoliticises the process, letting expertise, not patronage, lead. Second, and more radically, citizens must draw ward boundaries, with the commission as referee and not the drafter. Wards—over 1,450 of them—are the heartbeat of local governance, yet they are dictated top-down. I envision town halls, digital platforms, and community assemblies where people map their own lines, grounded in their realities.

Residents could propose splitting wards to ease representation strains, factoring in roads, markets, and clan ties. The commission wouldn’t impose—it would validate, ensuring proposals fit legal quotas and fairness. New Zealand’s model, where communities suggest boundaries and a commission refines them, proves this works. In Kenya, devolution’s county structure offers a ready scaffold—let the people build on it.

This isn’t utopian fantasy; Yes, challenges loom. Ethnic blocs could hijack forums, as Rift Valley history warns. Rural digital divides (54 per cent internet access in 2023) and low civic literacy demand investment. But these are surmountable with education campaigns.

The missed 2024 review is a wake-up call. Without it, 2027 elections will lean on outdated boundaries, amplifying disparities. A separate commission could reset the clock, expediting a late review by 2028.

Citizen ward adjustments could bridge the gap, offering relief without breaching the 290-constituency cap. Legally, this needs a constitutional tweak—Article 89 rewritten, a Boundaries Commission enshrined. Politically, it’s a fight; elites thriving on gerrymandering will resist. But public frustration is a potent weapon.