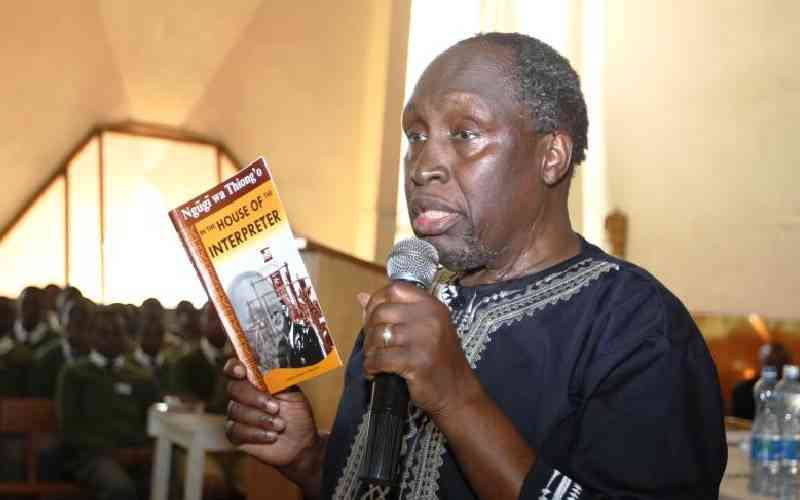

As a young university student slightly more than two decades ago, I wrote in an earlier incarnation of this page what I thought was a stinging criticism of the then fixation with Ngugi wa Thiong’o and other older writers back then. I touched several raw nerves at a time when critics were outdoing themselves in condemning publishers, panels that selected set books for high school and just about everybody for according preference to older, well-known writers at the expense of new ones.

While today I strongly believe we are not doing enough to identify and nurture upcoming talent, especially in the literary field, allow me to share the words of one Nderitu Ciuri. After reading my piece back then, Ciuri — I don’t know him — wrote back a small piece that ended in a few words that will follow me all days of my life and perhaps beyond the grave. “By trying to belittle Ngugi,” Nderitu wrote, “Munene runs the risk of belittling himself.” Crisp, bare knuckle and delivered as coldly as what we used to call a ‘sucker punch’.

The words of Nderitu came flooding back to my mind after the death of Prof Ngugi earlier this year. In typical fashion, the blogosphere was aflame. While some hailed Ngugi as one of Africa’s literary heroes, the ad hominem suckers went into overdrive. I saw a piece circulating on why his works were not fit to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The viral piece also argued why it was hypocritical of Ngugi to write in Gikuyu and then have his work translated into other languages, along with a few parochial assertions masquerading as literary analysis. Someone even faulted the good professor’s choice of how to go into what Dylan Thomas famously called the silent night yonder.

For me the problem was not criticising Ngugi and the older folk. While this is not an apologia for their works, I believe it is the place of literary discourse to bring new perspectives to the interpretation of the choices that our writers make and the works they churn out. That said, with the time I have come to see the point of living and letting others be. For, while we were taught that literary appreciation and criticism is not about singing praises for authors, I know it is also not a below-the-belt free-for-all where we hide behind esoteric linguistic gymnastics to hide our petty prejudices about those whose fame we wish could just rub off on us.

For me, and I take this line unapologetically, it is ignorant to rank African and indeed world writers by their perceived greatness. I do not have to say who is the best writer in Kenya of all time. For Grace Ogot, Jennie Marima, Meja Mwangi, Okello Nyandong, Henry ole Kulet, Odipo Sidang, Mwangi Gicheru, Pauline Keah, Makena Onjerika and other Kenyan writers all play a key role in shaping the rainbow that is the moving literary history of Kenya. It reminds you of the words of Chinua Achebe, who, when asked which of his works he considered the finest, said that he looked at his works like a paterfamilias would look at all his children. In that case, and these are not his words, there is the one who is obedient, another is bright in school, another one radiates the kind of warmth that reminds you of your grandmother and there is also that other of your children who is an outlaw waiting to cause trouble at the slightest provocation. Long story short, a writer’s works both excel and fall short depending on the yardstick you use to estimate their worth. In the words of Achebe himself, life — and literature — is a mask dancing; you see it from many sides. He, too, taught us that we all don’t have to write in one language or style, as where one thing stands today, another thing would be standing there otherwise.

Perhaps softened by age, I have come to like this multi-dimensional approach to assessing literary quality. For, while the older writers have done a marvellous job of painting for us an artistic picture of the fears, hopes and aspirations of those who came before us, it is to those who come after us that we owe the duty of literary care, which includes nurturing talent and paving the way for the next generation of literary greats. Unfortunately, the world is not what I want it to be. And I guess that is ok. All I ask is that instead of vilifying our own writers and splitting hairs on why they did not win this or that award, perhaps it would not be too much to ask that we at least honour their part in creating the beautiful tapestry that is African and world literature. I have listened to panellists at various forums going on and on about the weaknesses in modern African writing. I have heard the view that young writers are impatient and lack the literary finesse of older writers. That is preposterous, considering that our young upcoming writers live at a time when the battle for the next meal and other basic needs does little to fire up literary imagination. Yet as this gaslighting continues, we are reading of our young people winning prestigious awards in other parts of the world, meaning that we may be doing poorly when it comes to identifying and nurturing new talent.

Again, look at the history of Africa. In the 60s and 70s, our literary tradition was modelled on the European canon. That is why many people who went to A-levels back then quote Shakespeare as a matter of course. There were other variations, such as whether a country had been colonised by France, Britain, or other European ‘powers’. In my view, this diversity in terms of literary epochs, geopolitical influence on writing and so on is something to celebrate. It thus rings ignorant for someone to hold up the failure by such-and-such a writer to win this or that award as evidence of the inferiority of their writing. For, aren’t different awards meant to promote a specific aspect of writing? Must we all struggle to fit our writing into any one of these typologies? And doesn’t judging our art based on its conformity to other traditions unfairly seek to fit us into a fake global straitjacket that cannot even beginning to mirror our hybridised reality as a global village? In my shameless view, world literature is made beautiful by its diversity, not by a hierarchical illusion that smacks more of self-hatred than understanding. I rest my case.