Drug abuse among young people in Kenya is a deeply troubling and steadily growing public health concern. This alarming trend not only threatens the physical and mental well-being of individuals, but also has far-reaching consequences for families, schools, and society as a whole.

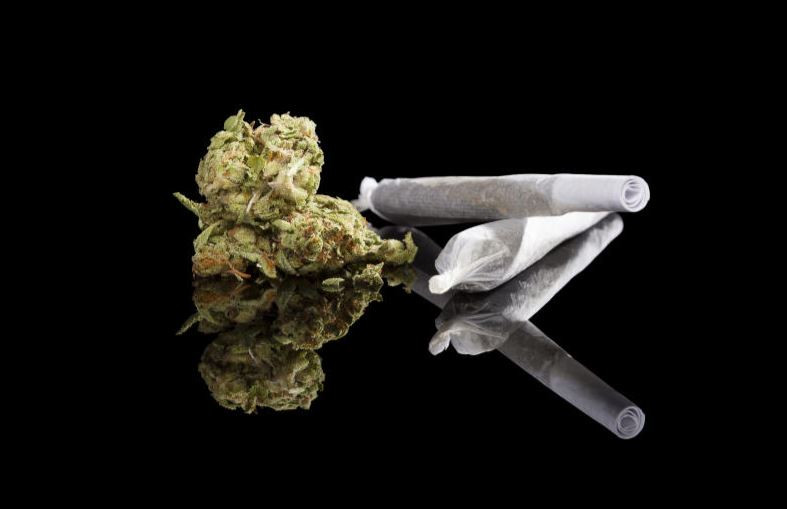

“I started using drugs in Form Two during the school closures brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic,” recalls Elkannah Koroso, now 21. “It was bhang,” he adds quietly.

Elkannah’s story is far from isolated. According to the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA), more than 500,000 young Kenyans between the ages of 15 and 24 are currently grappling with substance use disorders. Cannabis is the most widely abused drug, followed by alcohol, miraa (khat), and harder substances such as heroin and cocaine.

Dr Boniface Chitayi explains that the term “cannabis addiction” has now been replaced with “cannabis use disorder”. “Cannabis use disorder, like many other forms of substance abuse, often begins with experimentation,” he says. “This may develop into recreational use and, for some, progress into a disorder where the individual loses control.”

He notes that not everyone who experiments with cannabis will develop a disorder, as the progression depends on a combination of individual factors, including biological, psychological, and social influences. These risk factors may include a genetic predisposition, chronic stress combined with poor coping skills, and peer pressure. Young people who begin using cannabis early and do so frequently are, especially vulnerable.

In Elkannah’s case, peer pressure was the main trigger, a desire to fit in with friends from Nairobi who glamorised drug use.

“They used to talk about kuchoma (smoking) and partying in the streets. I just wanted to be part of the group. We used to do it late at night while others were asleep. I got used to it. In fact, I loved it,” he admits.

- How drug abuse threatens fight to end Aids deaths, HIV infections

- How needle sharing, risky traditions are fuelling hepatitis crisis

- Alcohol can seriously affect a young brain

- UN boosts Kenya's fight against drugs with 30 new testing kits

Keep Reading

According to NACADA’s 2022 Status Report on Drugs and Substance Abuse in Kenya, the situation is dire: One in every five Kenyan youths has tried a drug by the age of 19.

In counties, such as Nairobi, Kisii, and Kisumu, drug dealers have found easy access to secondary school students. School fences often serve as drop-off points for drugs, and dormitories are quietly turned into hidden drug dens.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has also issued warnings about the long-term impact of early drug use. A 2023 WHO bulletin on youth mental health in Africa states: “Substance use during adolescence interferes with brain development, increasing the risk of depression, psychosis, and engagement in risky behaviour.”

David Ouma, 24, from Oyugis in Homa Bay County, shares a hauntingly familiar story. “I was a heavy smoker back in Nairobi. Cannabis was my daily fix,” he recalls. “The Covid-19 pandemic made things worse. I was isolated, idle, and broke. Drugs became my only companion. There wasn’t a single day I went without them,” he adds.

Like many others, David’s journey into addiction began with peer pressure. “I used to smoke every day with my friends, who were already deep into it. They made it look normal, even cool. I thought they were doing the right thing,” he says.

“At first, I didn’t feel anything and almost gave up, but they convinced me to keep going. They said the high would come with time. So I listened… and kept smoking. That was around 2022,” he continues.

By the end of that year, David was fully dependent on cannabis. He narrates; “I couldn’t function without it. I needed it to start my day, to sleep... to do anything. It gave me this strange energy I had grown to crave. I even started mixing it with food, sprinkling it into whatever I was eating. That’s how far it went.”

For both David and Elkannah, the consequences of addiction came quickly, and painfully. Elkannah, once a high-achieving student with a solid B+ average, watched his grades fall to a C–. “My mother didn’t know what was going on. I only told her after I failed the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) exams,” he admits.

Dr Boniface Chitayi outlines the toll cannabis takes on the body and mind. “Physically, it can cause lung inflammation, persistent coughing, chest pain, and significantly raise the risk of lung cancer. It also increases the risk of cardiovascular conditions, such as high blood pressure, heart attacks, and strokes. Mentally, the most severe consequence is psychosis. But even before that, frequent use can lead to anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders,” he says.

Dr Chitayi continues; “Cannabis impairs one’s ability to function. It affects concentration and memory. Many users spend hours chasing the next high, neglecting school or work, and damaging their relationships through mood swings and erratic behaviour.”

Yet, both Elkannah and David managed to reclaim control over their lives.

“I quit last year,” Elkannah shares proudly. “I went for counselling and stayed clean from February to June. Now, I’m back in university with a renewed sense of purpose.”

David echoes that sentiment. “My church pastor and some friends sat me down and spoke to me about the dangers of drug abuse. At first, I thought they were just nagging. But over time, I saw they truly cared. I’m no longer an addict. A friend gave me a small amount of money, and I used it to start a poultry business. That’s what I’m focused on now, rebuilding my life.”

“Quitting saved me. I’m mentally clearer and emotionally stronger. Back then, every shilling I had went into weed or alcohol. Now, I’m investing in myself and my future,” he adds.

Unfortunately, their stories of recovery are the exception, not the rule. Most young addicts in Kenya don’t have access to the help they need. NACADA reports that of the 1,200 rehabilitation centres in the country, only 14 are government-run and affordable. The rest are private facilities, financially out of reach for most families.

Dr Chitayi explains the challenges that make recovery so difficult; “When people try to quit, they often experience anxiety, low mood, insomnia, poor appetite, and intense cravings. Without support, these symptoms can lead them back to drug use. That’s why professional intervention is crucial. A personalised treatment plan, counselling, and support from family or peer groups can make all the difference.”

He advises those in recovery to explore new hobbies, especially those that involve social interaction, to help replace the void left by drugs.

Elkannah believes government action is overdue. “We need more awareness in schools, not just warnings, but real conversations about drugs and mental health. Most importantly, we need accessible rehab centres where young people can go without fear or shame.”

David agrees. “Young people are turning to drugs, because they feel hopeless. There are no jobs, no opportunities, and nobody’s talking about the mental health crisis. If we keep ignoring this, we risk losing an entire generation.”

Dr Chitayi says cannabis use disorder is treatable with the right approach. This includes medical support for withdrawal symptoms, psychological therapies to help individuals cope with stress and triggers, and social rehabilitation through support groups like Narcotics Anonymous. It’s also vital to treat any underlying mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety.

“Cannabis use disorder is a disease, not a moral failing. People who are struggling deserve compassion, professional care, and space to heal. Whether they’re students or workers, they need time off to recover and support from their communities. A proper psychiatric assessment is the first step in helping someone rebuild their life,” Dr Chitayi says in conclusion.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print

operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a

leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national

and international interest.