At the back of his mind, Abdullahi Noor carries a story that refuses to fade, a tragic reminder of what drug and substance addiction can do.

As a harm reduction advocate, Noor has encountered many heartbreaking accounts, but one in particular continues to haunt him.

“I will never forget those two brothers. It is a story that has stuck with me for years,” Noor told The Standard.

The elder brother was already deeply entrenched in heroin use and living with HIV, a secret he kept even from those closest to him.

One day, the younger brother, who was still new to drugs but already hooked, was desperate for a high. He rushed home only to discover he had dropped his stash of bhang and the tobacco he was snorting. Overwhelmed by the urge to indulge, he stormed into his brother’s room and demanded a share of the substance, only this time, through injection.

“He demanded to use the same needle,” Noor recalls. “His brother, concerned for his safety, tried to stop him and revealed that he was HIV positive. But the younger one wouldn’t listen. He became violent, pulled out a machete, and insisted. The elder brother, frightened and worn down, eventually gave in,” Noor said.

The younger sibling injected himself with heroin using the contaminated needle. Shortly after, he tested HIV positive. Though he began treatment, addiction took hold. He dropped out of care and died from Aids-related complications in 2020 at the age of 25.

The elder brother, consumed by guilt and still battling addiction, passed away a year later aged 38.

Noor, the founder of Ngaza Mwangaza Global, a rehabilitation centre, met the brothers while he was also undergoing recovery from drug addiction.

“Had that needle not been shared, perhaps they would still be alive. Two lives lost because of one needle. That is how unforgiving addiction is,” Noor says.

This sorrowful story reveals more than a personal tragedy. It reflects a national crisis. Drug abuse is threatening Kenya’s progress toward ending new HIV infections and Aids-related deaths by 2030, with at least twwo in every ten people who inject drugs testing HIV positive.

Data by the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (Nacada), shows that at least one in every six Kenyans aged between 15 and 65 years, representing 4.7 million, abuse at least one drug or substance.

Men are disproportionately affected, with one in every three males actively using drugs, compared to one in every 16 females.

The Coast region, where heroin use and needle sharing are prevalent, has among the highest rates of multiple drug use at 10.5 per cent, followed closely by Nairobi and Central regions.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The report also indicates alarming increases in the use of cannabis, which has nearly doubled in the last five years, with Nairobi, Nyanza, and Coast recording the highest prevalence.

Cannabis use has also increased by 90 per cent in the last five years, with Nairobi leading in usage.

Meanwhile, prescription drug misuse and polydrug use (using multiple substances simultaneously) are rising concerns, with at least one in every 15 Kenyans engages in polydrug use, with Coast region showing the highest prevalence at 10.5 per cent.

These trends, experts warn, not only strain public health systems but also amplify the spread of HIV, especially among people who inject drugs, with at least two in every ten people who inject drugs in Kenya are HIV positive, further entrenching drug use as a driver of new infections, a direct threat to Kenya’s 2030 goal of ending HIV as a public health threat.

In Kenya, 1,378,457 people are living with HIV, with high prevalence reported among the key population, including two out of ten among people who inject drugs.

Data and studies show that people who inject drugs fall under the category of key populations, alongside men who have sex with men, transgender individuals, and female sex workers.

These groups face a significantly higher risk of acquiring new HIV infections compared to the general population.

In the recent past, key populations have contributed disproportionately to new HIV infections. In 2011, they accounted for nearly 33 per cent of all new infections in Kenya.

Nairobi records the highest number of HIV infections linked to injecting drug use, followed by Kilifi, Mombasa, Lamu, and Kwale.

Inland counties like Uasin Gishu and Nakuru are also witnessing an upsurge in drug use and related HIV cases, a trend attributed to increased connectivity through the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) and the general opening up of inland Kenya.

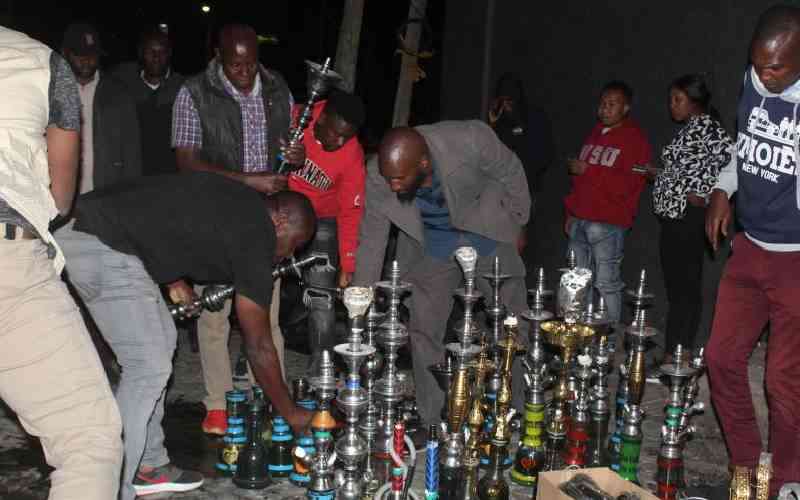

“We have concentrated efforts along the Coast due to high drug use, but we are also seeing increased access to drugs in other counties. We are addressing this in coordination with NACADA and local administrators,” says Douglas Bosire, the acting CEO of the National Syndemic Diseases Control Council (NSDCC).

The trends, he says, remains a major concern as Kenya works toward the goal of ending new HIV infections by 2030.

“The new infections tell us that we are not closing the tap. We may be mopping the floor, but unless we stop the flow, unless we close the tap, we will keep mopping endlessly,” said Dr Bosire.

To address this, NSDCC runs a needle and syringe programme under the harm reduction approach.

This initiative provides clean injecting equipment to people who use drugs to discourage sharing, a key driver of HIV transmission.

“We supply needles and syringes to reduce the risk of infections. It is about minimising harm while working toward rehabilitation,” added Bosire.

In addition, individuals enrolled in the harm reduction programme are also placed on methadone therapy to help wean them off hard drugs.

The programme is a collaborative effort involving NSDCC, NACADA, the National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP), and local administrative units.

Thanks to these interventions, the proportion of new HIV infections attributable to people who inject drugs has dropped from 33 per cent in 2011 to 13 per cent in 2022.

HIV prevalence among this population also showed a notable decline, from 19 per cent in 2022 to 11 per cent in 2023.

Despite these gains, many individuals undergoing rehabilitation struggle with reintegration and face social stigma. In response, NSDCC and NACADA are working closely with local administrators, religious leaders, and county governments to support community acceptance and inclusion.

The harm reduction programme is currently active in coastal counties, including Mombasa, Kwale, Kilifi, and Lamu, focusing on helping drug users overcome addiction and reintegrate into society.

Furthermore, NSDCC is mobilizing resources to empower recovering drug users economically and train them as peer educators, turning them into agents of change within their communities.

Reach Out Center founder Taib Abdulrahman attributes substance use in Coastal region to drug trafficking through the Indian Ocean, porous borders, air, and sea routes.

“We have become a hub for heroin trafficking, and over the past two decades, we have witnessed horrifying scenes, overdoses, needle sharing, and broken families caused by drug and substance abuse,” Taib says.

Taib notes that the average age of drug users has alarmingly dropped, with use cutting across different levels of social-economic status.

“In the past, the average age was 25. Today, it is as low as 15. Many children have dropped out of school, and sadly, every homestead you visit in some areas will likely have someone affected by drug use—, either a father, mother, or child.”

Wangai Gachoka, the manager of Miritini Rehabilitation Centre of Excellence and Coastal region coordinator for Nacada, says the entity in collaboration with NSDCC and Nascop, runs a harm reduction programme that includes distributing clean syringes, offering methadone, and providing free condoms.

The goal of the programme is to reduce infections of HIV, Hepatitis among other diseases, ad support recovery of addicts.

“If users stop sharing needles, HIV transmission will go down significantly,” Rev Gachoka explains. “And if they are sexually active, which often happens with drugs like miraa and muguka that increase libido, we provide condoms to prevent further spread,”Gachoka says.

Miritini Centre currently supports at least 359 individuals on methadone treatment daily, with some living with HIV, according to the Nacada official.

The rehabilitation centre receives a wide range of care, ranging from antiretroviral therapy (ART), PrEP, and treatment for TB, malaria, and Hepatitis B and C.

“The facility operates as a one-stop centre, especially for individuals who are homeless or face stigma in hospitals,” says the coordinator.

While heroin and cocaine remain serious threats, Gachoka warns that miraa and muguka are increasingly damaging Kenya’s youth, particularly those aged between 18 and 35 years.

“Miraa and muguka are stimulants. They activate the brain, increase libido, and when combined with other drugs, create a dangerous cocktail. The problem is—they’re cheap, legal, and easy to access,” he says.

In rehabilitation programmess at Miritini, miraa and muguka rank second only to alcohol in terms of substances abused.

Worse still, these substances are often combined with prescription depressants bought illegally from unethical pharmacies.

“Some pharmacies sell psychotropic drugs without following the law. We’re working with the Pharmacy and Poisons Board and other agencies to crack down on these illegal sales.”

Gachoka emphasises that methadone alone is not enough, it must be coupled with counselling, therapy, and spiritual support.

“When someone uses heroin, they become like a zombie. But with methadone and counseling, they start to function. They can work, think, and live again.”

The Miritini model includes psychosocial support, spiritual care, and vocational therapy to ensure holistic healing. Clients are also provided with clean facilities where they can shower, rest, and regain dignity.

Gachoka believes Kenya’s drug crisis needs more than just treatment—it needs prevention and policy reform.

“Accessibility is the biggest problem. If people didn’t have access to these drugs, fewer would be hooked,” he says. “We must tighten supply chains, regulate pharmacies, and address peer pressure and emotional trauma that lead people to drugs in the first place.”

At the centre, The Standard meets Brian* Mtwapa in Kilifi District, Mombasa County who carries the weight of a life shaped by early hardship and addiction — but also, today, a life marked by resilience and hope.

Brian’s battle with heroin addiction began when he was only 10 years old. Forced to drop out of school in Standard Three due to lack of school fees, he started working for drug traffickers, packing heroin smuggled in from a neighbouring country.

Curiosity soon led him to try the drug, a decision that spiralled into daily dependence.

“I started using heroin when I was about 10,” Brian recalls. “Instantly, I got hooked. I injected the drug through veins in my head, hands, legs — even my private parts.”

For the 46-year-old addiction escalated quickly, with Katana using up to two grams of heroin a day.

Aggressive injection practices led to severe vein damage and infections, eventually requiring surgery. Repeatedly sharing needles also exposed him to Hepatitis B infection.

“When you're intoxicated, you don’t think about whether the needles are safe,” he says. “All I cared about was getting high — but it cost me my health. I ended up contracting Hepatitis B.”

Now undergoing treatment and rehabilitation, Brian is focused on healing — and on helping others understand the devastating consequences of drug abuse.

Prof Omu Anzala, a virologist at the University of Nairobi notes that all needles are disposable- “used once and discarded”.

Currently, he says syringes and needles cannot be sterilised, unlike in the past- “they are all plastic, cannot be sterilised for re-use. They have no ability to sterilise”.

The virologist who has been in HIV research, however, regrets that whereas needles are single-use, drug addicts are using them, risking transmission of pathogens carrying HIV, Hepatitis C and B.

A number of drug users collect syringes and needles from hospitals waste. To avoid such, hospitals are encouraged to incinerate their waste.

“Nobody in any hospital reuses needles. But we are witnessing young men addicted to drugs hiding on streets, injecting themselves,” regrets Anzala. “They re-use needlers, enhancing HIV infections, Hepatitis B, C and other pathogens found in blood”.

A person who injects drugs, Prof Anzala says, has the possibility of transmitting blood that contributes to HIV transmission.

“When you inject yourself in the muscle and remove it, there is blood left in the syringe. It is direct exposure to infections. The needle might be carrying blood,” he says.